Calling Them Names: Michael Endlichers Shouting 130 Words Against The Light

(English version below)Ein Mann betritt eine kleine Bühne in einem dunklen Kinosaal. Er klettert etwas unbeholfen auf ein säulenartiges Podest und beginnt etwas zu deklamieren. Das weiße Licht des Videobeamers blendet ihn. Es strahlt die Leinwand hinter ihm an, auf der sich sein Schatten abzeichnet. 130 Worte spricht, schreit er in diesen Lichtstrahl, während das Publikum gebannt zuhört. Es hat ein Blatt mit diesen 130 teilweise abgekürzten Namen beim Eingang zu Beginn der Performance erhalten. Kann diese aber ob der Dunkelheit im Saal nicht mitlesen. Es wird die fünf Spalten später überfliegen und versuchen, sich zu erinnern. Nach dem alles ausgesprochen ist, klettert der Mann von der Säule und verlässt die Bühne.

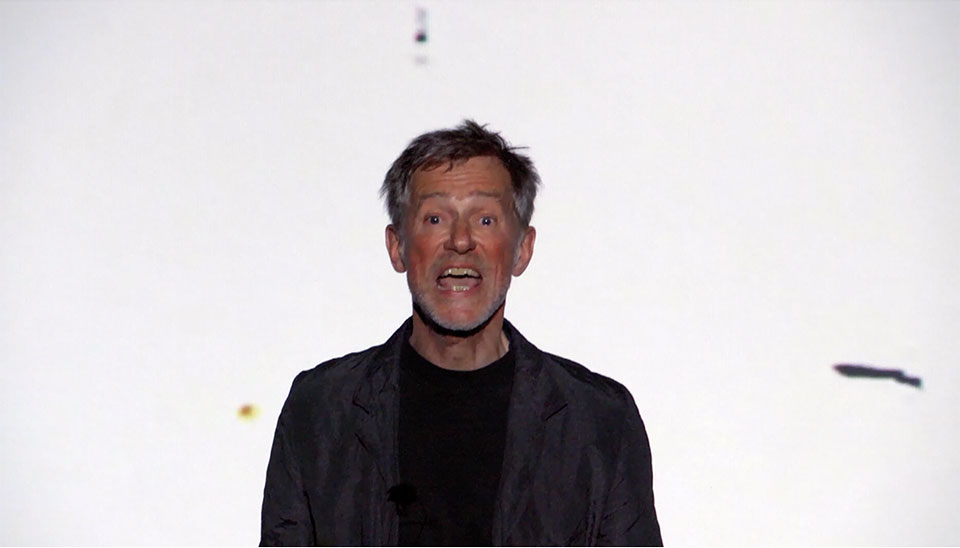

Ein paar Wochen später gibt es eine editierte Videoaufzeichnung dieser Performance, die im Mai 2019 im Kino des Belvedere 21 stattgefunden hat, auf der Online-Plattform des Blickle Video Archivs zu sehen. Diese verschiebt den Blick, denn die Zuseher*innen sehen nun, auf dem Bildschirm, etwas Anderes als damals im Auditorium. Sie sehen womöglich die Anstrengung, die im Memorieren der Zeilen liegt, wie das weiße Licht, das den Performer unangenehm blendet. Sie konzentrieren sich auf das Gesicht, das „Affektbild“ (Deleuze), das den Affekt überträgt. Die Präsenz der Stimme jedoch, die aus dem Körper kommt und das Gesagte schließlich in den realen Raum zu den Anwesenden trägt, bleibt seltsam unbedeutend in diesem, den Sehsinn bevorzugenden Medium.

Ich beginne nochmal: Die 130 Namen mythologischer Gestalten, die Künstlernamen, Vornamen, Markennamen und Schimpf(namen)wörter, die der Künstler Michael Endlicher in seiner Performance (und später im Video) dem Projektor-Licht entgegenschreit, könnten, in Zeiten wie diesen, natürlich leicht auf das grassierende Corona-Virus umgemünzt werden. Das Ganze ist aber lange davor passiert, obgleich die Performance bereits Bezug auf den Ausdruck und die Performativität einer Unzufriedenheit nimmt, die sich bis in die Gegenwart verfolgen lässt.

Ausrufen

Anrufen

Verrufen

Calling them Names beruht auf einer (meiner) falschen Übersetzung, denn natürlich heißt es nicht auf Deutsch „sie mit Namen rufen“, sondern schlicht und einfach „jemanden beschimpfen.“ Doch kommen mir diese „falschen“ Namen sehr gelegen, denn wo hört die Anrufung auf, wo beginnt das in Verruf bringen oder Beschimpfen?

Namen stellen signifikante Faktoren für die Konstruktion von Identität dar. Nach Jean-Francois Lyotard bezeichnet der „richtige Name“ die Realität eines Menschen, seine Einbettung in eine Kosmologie, die ihn als Subjekt etabliert, aber dadurch gleichzeitig prekär ist. Denn der Name selbst jedoch kann laut Lyotard nichts offenbar machen, er ist nur ein unzulänglicher Referent.[1] Um eine Beziehung zwischen diesem und der Realität, die er bezeichnen soll, aufzubauen, müsse ein komplexes System an sprachlichen Operationen „ausgerufen“ werden,[2] was die Beziehung jedoch nicht stabiler macht. Was passiert nun, wenn sich dieser Referent ändert oder geändert wird? Dann verschiebt sich das gesamte System des „Benennens, Zeigens und Bedeutens!“[3]

Im ausgeteilten Saalzettel stehen die Namen, die Endlicher ausruft, nebeneinander und werden dadurch gleichgesetzt. Egal ob „Nike“ oder „Amun“, „Dali“ oder „Visa“, es gibt keine Hierarchie. Strukturell sind sie alphabetisch geordnet und auf vier Buchstaben verkürzt. Auf der Ebene der „Erzählung“ wirft dies die Frage nach dem Ursprung und dem etymologischen Gehalt eines Namens auf, offenbart den historischen Horizont sowie den sich verändernden Kontext: Wann und warum wird ein Name zur Marke? Wann wird aus einem Namen ein Schimpfwort? Wann wird ein Schimpfwort unaussprechlich?

Der Performancekünstler James Lee Byars, den Michel Endlicher als einen seiner künstlerischen „Vorfahren“ für manche seiner Arbeiten nennt, spricht in einer Rede am Nova Scotia College of Art and Design 1971 von der Schwierigkeit, Fragen zu formulieren: „I mean, there are questions where you’re taught the answer before the question, and then you’re asked the question and you raise your hand and the teacher thinks that’s a big deal. That kind of question is defeating. And so I wondered - is all speech interrogative?”[4]

Die vorher erwähnten Fragen stellen sich durch Form und Struktur der Performance. Was aber, wenn nun, viel unmittelbarer, die Namen Fragen sind, die der Künstler ins Auditorium schreit? Wer sind denn die Adressat*innen dieser Fragen? Sind wir diese Angerufenen, das Publikum, die Zuseher*innen? Begreifen wir uns als Stellvertreter*innen für die mit „Dolm“, „Ratz“ und „Uole“ gemeinten? Hier könnten wir mit Lyotard antworten: „Ja, aber … der Name bedeutet ja nichts, er ist nur die Spur einer bezeichnenden Funktion,“[5] und uns nicht weiter angesprochen fühlen.

Doch tritt bei Shouting 130 Words Against The Light live – im Gegensatz zur Video-Aufzeichnung, die das Publikum eher ins Off verweist - etwas Entscheidendes hinzu: die Verbindung von Performance und Performativität. Denn sowohl der Körper des Performers und dessen singulärer Ausdruck wie auch die Wiederholung eines Musters, eines Sprechaktes, durch den sich die Signifikationsprozesse ändern oder zumindest im Fluss bleiben, tragen zur „Verkomplizierung“ einer Form bei, die andernorts bloß als stark verkürzte Schmährede wahrgenommen werden würde.[6]

Die Affizierung des Künstlerkörpers, der sowohl sich selbst als auch die unterschiedlichen Referenzen an Vorbilder, die „Rolemodels“, spielt und hierbei sowohl authentisch, sowie das komplette Gegenteil davon ist, überträgt sich durch die Performance auf die Zuseher*innenkörper. Es wird mitgefiebert, gelacht, der Atem bei jedem Stocken des Künstlers angehalten, verhalten geschmunzelt, spöttisch geblickt, erleichtert applaudiert. Gemeinschaft entsteht im Zusammensein der Körper, die eben nicht nicht kommunizieren können.

Es ist ein äußerst fragiles Künstlerbild, das sich in Shouting 130 Words Against The Light wie in vielen von Michael Endlichers Arbeiten zeigt. Was auf den ersten Blick oft provokant wirkt, lässt im körperlichen Ausdruck, dem „grain of the voice“ (Barthes), die Zerbrechlichkeit und Ratlosigkeit angesichts der Frage, was Künstler*in-Sein bedeuten kann, bewirken kann, durchscheinen.

Claudia Slanar, Kunsthistorikerin, leitet seit 2024 die Diagonale. Zuvor war sie Kuratorin des Blickle Kino/Video Archivs im Belvedere21, Wien.

[1] Siehe Jean-Francois Lyotard, “The Différend, The Referent, And The Proper Name,” Diacritics 14.3 (Fall 1984): S. 10ff.

[2] Ibid, S. 13.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Siehe Lucy Lippard, Six Years: the dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972, Berkeley/ Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1997 (1973), S. 165.

[5] Lyotard, S. 10

[6] Die literarische Form der Schmährede soll hier nicht geschmäht werden, gibt es doch gerade in Österreich eine Tradition der Beschimpfung, Wut- oder Brandrede. Der „Wutbürger“ als massenmediales Phänomen taucht zu Beginn der 2010er Jahre als Phänomen der Mittelschicht auf, um in den letzten Monaten in unterschiedlicher Verkleidung wiederzukehren: Impfskeptiker, Maskengegnerin, Staatsverweigerer, etc. Oft wird der Zorn als durch und durch „authentisch“ missverstanden und nicht als Performance. Im Unterschied zu letzterer im künstlerischen Feld jedoch wird diese Verkleidung als Mittel zum Zweck verstanden, die Botschaft als Problem des Empfängers. Nie geht es um das Spielen mit und gegen den Text oder die permanent neu auszuhandelnde Form der Bedeutungsproduktion von Sprache. Zu dieser Diskussion siehe etwa Paul Divjak, Thomas Edlinger „Wut und Wahn. Erregungsmanagement in zornigen Zeiten,“ Der Standard, 16.12. 2011, https://www.derstandard.at/story/1323916618025/wut-und-wahn, eingesehen am 20.5. 2020. Oder Ronald Pohl, „Wut ist die größte Kraft von Österreichs Dichtern,“ Der Standard, 16.5. 2020, https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000117516795/wut-ist-die-groesste-kraft-von-oesterreichs-dichtern,

eingesehen am 29.5. 2020. Erwähnung soll hier auch der von der Schriftstellerin Lydia Haider herausgegebene Band „Und wie wir hassen!“ (Kremayr & Scheriau, 2020) finden, indem sie durchwegs weibliche Brand- und Hassreden versammelt.

Calling Them Names: Michael Endlicher’s Shouting 130 Words Against The Light

A man enters a small stage in a dark cinema auditorium. Somewhat awkwardly he climbs a columnar pedestal and starts declaiming. He is blinded by the white light of the video projector. It illuminates the screen behind him so that his shadow can be seen. He says, shouts 130 words into this beam of light while the audience is listening, spellbound. At the entrance, before the beginning of the performance they have received a sheet with these 130 partly abbreviated names. However, due to the darkness in the auditorium they cannot read along. Later on they will scan the five columns and try to remember. After everything has been said, the man climbs down from the column and leaves the stage.

A few weeks later, the online platform of the Blickle Video Archive shows an edited video recording of this performance, which took place in May 2019 in the cinema of the Belvedere 21. This recording shifts the spectators’ view because they now see something different on the screen than they did at the time in the auditorium. They might see the effort of memorising the lines, as well as the white light which blinds the performer disagreeably. They concentrate on the face, the “affect picture” (Deleuze) that is transferring the affect. However, the presence of the voice coming out of the body, carrying on what is being said into the real space to those present, remains strangely unimportant in this medium that favours the visual sense.

I will begin once again: the 130 names of mythological figures, the names of artists, first names, brand names and derogatory names, which the artist Michael Endlicher shouts out against the light of the projector in his performance (and later on in the video), could, at times like these, easily be translated to the raging Corona virus. But it all happened long before, although the performance already refers to the expression and the performativity of a feeling of dissatisfaction which can be traced into the present.

Calling out

Calling on

Calling down

Calling Them Names is based on a wrong translation (by me), because in German this does not mean “to call them by their name” but plainly and simply “to insult someone”. Yet, these “wrong” names come in useful for me because where do we stop to appeal, where do we start to discredit or to insult?

Names play a significant role in the construction of identity. According to Jean-Francois Lyotard, the “real name” refers to the reality of a human being, his integration into a cosmology that establishes him as a subject but thereby becomes precarious at the same time. Since the name itself cannot reveal anything according to Lyotard, it is only an inadequate referent. [1] In order to construct a relation between this referent and the reality it is intended to refer to, a complex system of linguistic operations has to be “called out” [2], which, however, does not make the relation more stable. But what happens if the referent changes or is changed? Then the whole system of “naming, showing and meaning” will shift.[3]

In the leaflet distributed in the auditorium the names that Endlicher is calling out are arranged next to each other and are thereby regarded as equal. No matter if “Nike” or “Amun”, “Dali” or “Visa”, there is no hierarchy. Structurally, they are arranged alphabetically and reduced to four letters. On the “narrative” level this questions the origin and the etymological content of a name, reveals the historical horizon as well as the changing context: When and why does a name become a brand? When does a name turn into an insult? When does an insult become unspeakable?

The performance artist James Lee Byars, who Michael Endlicher refers to as one of his artistic “ancestors” for some of his works, spoke in 1971 in a speech at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design about the difficulty of phrasing questions, “I mean, there are questions where you’re taught the answer before the question, and then you’re asked the question and you raise your hand and the teacher thinks that’s a big deal. That kind of question is defeating. And so I wondered - is all speech interrogative?”[4]

The questions mentioned previously are posed by the form and structure of the performance. But what if now, much more directly, the names are questions that the artist shouts into the auditorium? Who are the people these questions are addressed to? Are we, the audience, the spectators, these addressees? Do we see ourselves as representatives of those called “Dolm”, “Ratz“ and “Uole“ (nitwit, scum and hag)? Here we might answer with Lyotard, “Yes, but...the name does not mean anything, it is only the trace of an indicative function”[5], and not feel addressed any further.

However, in contrast to the video recording which rather places the audience aside, Shouting 130 Words Against The Light live contains something essential: the connection between performance and performativity. The body of the performer and his singular expression as well as the repetition of a pattern, or a speech act, which change or at least keep the processes of signification going, contribute to the “complication” of a form that would otherwise be only perceived as a significantly shortened diatribe.[6]

By representing himself as well as the different references to “role models” in an authentic but also a completely converse way, the pretence of the artist’s body is transferred to the spectator’s bodies during the performance. The audience share the excitement, laugh, hold their breath at every hesitation of the artist, guardedly smirk, mockingly watch, and applaud in relief. Companionship is created through the gathering of bodies that are simply not able not to communicate.

The image of the artist that manifests itself in Shouting 130 Words Against The Light is, like in many other works by Michael Endlicher, a very fragile one. In its physical expression, the “grain of the voice” (Barthes), what may often seem provocative at first sight, makes noticeable the fragility and cluelessness in the face of the question what it may mean and effect to be an artist.

Caudia Slanar, art historian, is festival director of the filmvestival Diagonale. Before she was curator at Blickle Cinema and Video Archive/Belvedere21, Vienna.

[1] See: Jean-Francois Lyotard, “The Différend, The Referent, And The Proper Name,” Diacritics 14.3 (Fall 1984): p. 10et seqq.

[2] Ibid, p. 13.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See: Lucy Lippard, Six Years: the dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972, Berkeley/ Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1997 (1973), p. 165.

[5] Lyotard, p. 10

[6] This does not intend to defame the literary form of diatribe, because especially in Austria there is a tradition of insulting, agitation and hate speeches. At the beginning of the 2010s the phenomenon of the “enraged citizen” appeared in the mass media as a middle class phenomenon, reappearing again in the last months in different disguises: vaccine sceptic, facial mask opponent, state objector, etc. Anger is often misinterpreted as authentic to the core and not regarded as a performance. However, in contrast to the artistic one, this disguise is seen as a means to an end, the message as the problem of its recipient. It is never about playing with and against the text or the production of meaning through language that has to be negotiated permanently.

In this context see for example:

Paul Divjak, Thomas Edlinger “Wut und Wahn. Erregungsmanagement in zornigen Zeiten (Anger and Delusion. Agitation management in angry times)“, Der Standard, 16.12. 2011, https://www.derstandard.at/story/1323916618025/wut-und-wahn, as of 20.5. 2020.

Or: Ronald Pohl, „Wut ist die größte Kraft von Österreichs Dichtern (Anger is the greatest force of Austria’s poets.),“ Der Standard, 16.5. 2020, https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000117516795/wut-ist-die-groesste-kraft-von-oesterreichs-dichtern, as of 29.5. 2020.

I would also like to mention the volume “And how we hate!” (Kremayr & Scheriau, 2020) published by the author Lydia Haider, a collection of entirely female agitation and hate speeches.